My Midlife Crisis

I have never been a practical person. This has led to the situation I now find myself in. My midlife crisis.

I saw the technological revolution in the '90s and I was a part of it. My father worked for Pacific Bell Internet as a technical analyst. That's a fancy phrase for tech support, or phone support. He encouraged me to apply. I got the job at age eighteen. I worked for PBI for almost two years. At one point, because of a shift-differential I was briefly earning more than my father at the same job. PBI was soon bought by SBC, a large communications company out of Texas. They imposed a long hiring freeze, and I burned out on answering phones. I forced them to fire me.

I looked for other work in the booming world of tech startups. I landed a job as a lead web developer in Burlingame. My manager would come over and push me aside and sit in my chair and screw with my work. After multiple times doing this, apparently I yelled at him. I told him to put his requests in my inbox. I don't remember how I said it, but I was fired on the spot. I filed a labor dispute but nothing came of it.

I staged a dubious rebellion against the technological revolution. Never was a joiner anyway.

I decided then that office work was for wimpy assholes who couldn't take criticism. I didn't like the HR games and I didn't believe in the products. So much corporate fluff. Unnecessary filler. Garbage. Though I enjoyed technology and programming computers, I thought the corporate workplace culture was fake and transient. At least in construction, you damn-well knew where you stood with the boss and co-workers, and you could look back at your day's work with pride.

There is a brotherhood in the trades. I knew this because of my early work with my father when he was a general contractor, and I was missing it. I was outwardly angry at him as a teen, but subconsciously I always idolized my father. He was a god amongst men in my mind. He began taking me to job-sites when I was eight years old until I was seventeen, and those experiences were burned into my memory forever.

So I picked up my hammer and tool-belt and went to work. I would walk on to local job-sites and ask for the foreman. Sometimes the foreman would stomp over to me, throw his helmet on the ground and tell me to get the fuck off his site. More often, the foreman would ask me to perform some task on-the-spot, like hammer a sixteen-penny nail through stacked 2x4s for example. The foreman watched me intently as I did this, and I either got the job or I didn't. I often did get the job.

When I was twenty-two, I lived in a dilapidated warehouse on the Emeryville-Oakland border. I didn't have a license or vehicle. I took the bus everywhere or rode my bicycle. My housemates were an annoying and slightly dangerous mix of artists, druggies, and transitory gutter-punks who rolled off freight trains in the middle of the night to get free tattoos from the meth-addict lease-holder.

Dealer's choice. You get what you get.

My first job in construction outside the family business was as a framing carpenter on a commercial site in Dog-town, a bad neighborhood in West Oakland. The company was Dream Builders, I think they are long gone now. We were building a seven story apartment complex with mezzanine shops down below. Except the first story, it was all wood-construction and the completed space was to be over 100,000 square feet.

I was the only white person on the crew. There were twelve Guatemalans, one Mexican, and me. The boss and foreman would take their lunches in their separate trucks. I would lunch with the Mexican guy, I don't remember his name anymore and the Guatemalans would lunch with each other.

Sometimes, I would arrive to work hung-over, without sleep, still drunk, or all three. I would find somewhere on the site to take a quick nap. Ten to thirty minutes was all I needed before lurching (under pain of death) back into action.

I started as a laborer unloading Gradalls, large forklifts with extended reach. They would hoist large loads of material arriving on semi-trucks up to the second or third story of the building. An example of this would be a stack of wet 20' 2x12s, or 4x10' sheets of 1 1/8" thick tongue-and-groove OSB (oriented strand-board) plywood. Each piece of material weighed at least as much as I did, 140 pounds. I was a wiry son of a gun, but I found the strength to do what I needed to do.

I was lightning wrapped in skin.

I had a big chip on my shoulder. I was mad at the boss, mad at my housemates, and mad my parents. I channeled my anger into my work. I could off-load three Gradalls by myself in an eight-hour day.

One time I stacked the material in the wrong place, underneath a diagonal wall-brace. The foreman came over, cussed me out, and helped me re-stack. It was a humbling experience. He ripped the 2x12s out of my hands so quickly I was getting splinters, but I didn't dare stop to inspect them. After we were done he asked me rhetorically where my gloves were. He looked down at my bleeding hands, told me to go to the first-aid kit, fix myself up and wear gloves next time.

The boss, a barrel-chested sixty year-old guy frequently yelled things at me punctuated by cuss words, "Take two!" or laugh and say "We all have compressed discs, and you will too," or "This work will make a man out of you. Well, (second glance) it will make something out of you." I took two pieces while he was watching, well-over two-hundred pounds in my hands. When he wasn't looking I went back to carrying one piece, but quickened my pace. To this day, one of my shoulders sits slightly lower than the other in resting position.

After a few weeks of this, he told me to put on my belt and pick up the nail-gun. We were framing at a rate of one-story per week. Pretty damn fast. We were already up five stories. He had me walk out on the width of a 2x4 top-plate on the edge of the building with a 16-foot long 2x12 which was probably at least 100 pounds in one hand and a nail-gun trailing an air hose in the other. I was supposed to attach it to the top-plate of a framed wall with no sheathing. It was quite wobbly as I put one foot in front of the other. There were no safety nets. A couple of diagonal braces were my only consolation against a sixty-foot drop to the ground.

I vividly remember a wind gust blowing sawdust up the face of the building into my eyes. I quivered and caught my balance with my severely unbalanced load. The whole crew had stopped work and was watching, laughing and hooting at me. The foreman told me I looked like ballerina. All I could manage was a crooked smile as my life precariously hung in the balance and I tried to attach the rim-joist with tannins from fresh sawdust stinging my eyeballs. I was finally a framing carpenter, but was it worth it?

All this for eleven dollars per hour.

I've done a bit of commercial work.

Since then, I have built the stands on Pier 29 for America's Cup. It was composed of giant channeled aluminum struts manufactured in Germany, instructions in Japanese, and with a French foreman reading them and shouting at us in a thick accent; I've installed megawatts of solar panels for Solar City and Real Goods Solar out of Marin; I've done hospital remodeling and construction; and worked on constructing the belts and scanners for a FedEx sorting facility; I helped build the Redfin hotel in Emeryville, but most of my experience in construction is in residential-remodeling.

I have worked for many dozens of small to medium-sized general contractors, primarily in the East Bay. Many of those outfits specialized in a certain aspect of construction, some were generalists working all-trades. There are not many new homes being built in the Bay Area. I like to say I learned how to build houses from the inside-out. I have been involved in every phase of residential home construction from grading and foundations to roofs. From framing to finish, and a bit of electrical and plumbing along the way.

Rounding out my job history since I was 18, I have been a mover unloading the contents of houses from semi-trucks. I have driven a ten-ton truck delivering dimensional redwood lumber all over the Bay Area with my foot to the floor. I've worked at local warehouses, lumber yards, stone yards, and a pre-cast concrete plant in Montana building septic tanks (that one-time when I followed a girlfriend to Bozeman). I've worked in a law office as a file clerk, the meat-counter at a grocer, and a couple bicycle repair shops as a mechanic. There are probably other jobs that I am forgetting, but that should give you an idea.

I tried the self-employment route: I got in with a real-estate appraiser as a handyman and finally made decent money in construction knocking out his punch-lists in San Francisco. In my twenties I ran a desktop support business briefly with limited success called Computer Cowboy.

I am a diligent worker, when I have work.

I could always get a job. My problem was keeping a job. I have always had a problem with authority, and I don't make it a secret. Also, I was battling alcoholism and depression for many years. My self-discipline was lacking because I was depressed and self-medicating. I was constantly questioning my very existence. Everything seemed to pale when put against that question, and it was always on my mind like an evil, smiling crescent in the sky.

There was a lot of time between jobs, and it was pretty demoralizing to lose each one after I had given it my all.

My life consisted of an almost continuous job search.

Suffice it to say I've banged my head against the wall for thirty years, and it has got me nowhere. Absolutely nothing. I might've been better off sitting on my ass.

I am of sound mind these days and I rarely drink to excess anymore, but I have been struck with various annoying physical impediments as I've gotten older (which I'm not going to outline here). I am approaching fifty, and construction is a young-man's game. I am able to get the job done. I can perceive the critical path of any task, and I throw myself down that path with abandon. I'm not frail but my body would surely betray me now if I had to keep pace with twenty-somethings.

My work history is spotty. I have worked close to one-hundred jobs in my lifetime and most of those were for cash under the table. No vacation, no medical plan, no pension, no 401(k), and I have not worked enough hours on-record to qualify for Social Security.

I am screwed, more or less.

On top of all that, for the last three years I have been unemployed. I feel as if I am strapped to the front of a locomotive that is running out of track. So pardon me if I scream into a pillow now.

I deeply regret some of my life choices. If I had to do it over again, I would've thrown myself at my creative pursuits with full-force right away. Everything has led me to this point though. My friend Chris Rogers says that I have a lot. And it's true, I am surrounded by friends and family, and I am making an impact in my community. Most days I am grateful for what I do have. Most days.

For the last five years I have been deeply involved in music production. I have been ramping up my tracking (recording and audio engineering), mixing and production skills over that time. I just had my first paying client for audio services last week! I hope it is the beginning of a new chapter for me in which I can do something I love, and get paid to do it. We shall see.

I have to say this, I am very fortunate to have a loving and compassionate family backing me up. They have never wavered in their love, support and faith in me. Jenny and Pascale are one-in-a-million.

I'd be on the street without them, probably succumbing to addiction and deteriorating mental health.

I'm glad to say I have managed to not screw it up where they are concerned. I am humbled and awestruck by their confidence in me. It is only through their love and stability that I have been able to launch new creative pursuits which are just now beginning to pay off.

I am counting on luck through hard work, and serendipity to see me through. Maybe that is foolish of me. But I think many people are in the same position just barely hanging on to a glimmer of hope. Living check to check, or off of dwindling savings.

The world is winding down just as the creative flux of my life swells, and it saddens me a little. I used to take on the weight of the world when I was a teenager. Or at least I felt that I had an empathic connection to the world back then. These days I get it off my shoulders.

I cannot take on the world and fight for myself at the same time. I still feel deeply about the world at-large, but I need to be able to function so I can be of service to my friends and family. So I shift my focus to my little sphere of influence.

In a sea of choices I have to focus to be effective within my lifetime. I think at 48 years old, I am just beginning to narrow my focus and make the right choices to move forward.

There is finally a speck of light at the end of the tunnel, and I am moving towards it.

I am quickly approaching a time in my life when most people are busy wrapping up long, successful careers. I am starting a new career, one that I don't know the shape of yet. There is no roadmap for how this goes. Time will tell. All I can say is I want to make music, photos and write until the day I die.

How I feel is a mixed bag. On the one hand I am super-grateful, I glad-hand everyone I meet. On the other it isn't enough. I am striving to better myself because I have the classic addict attitude of "more must be better." I've had a taste of the rewards of pursuing my passions, and I can't get enough. If the world shifted on it's axis even slightly, I could slip into catatonic depression and drown in my regrets. I walk a tight rope in my mind. It is a balancing act. I am aware that my time here is limited. I feel my mortality, that is part of what is driving me now.

No longer the youth that I was, I am still starry-eyed and full of hope and possibility.

Mine is a cautionary tale. If you are young and just starting out, or old and starting over, don't delay. Don't sell yourself short. Do what you love in the face of it all. Even if it's not the most practical thing. Strive. Push yourself. Don't wait for permission. No approval is forthcoming. Fuck it. Make bold moves. But most of all, be gentle with yourself.

Don't squander your incredible energy, precious time or fleeting money on someone else's dream. Build your own dream, brick-by-brick. Break it down into steps and do it. Otherwise you condemn yourself like I have to a life of labor and servitude, and it might not serve you in the end.

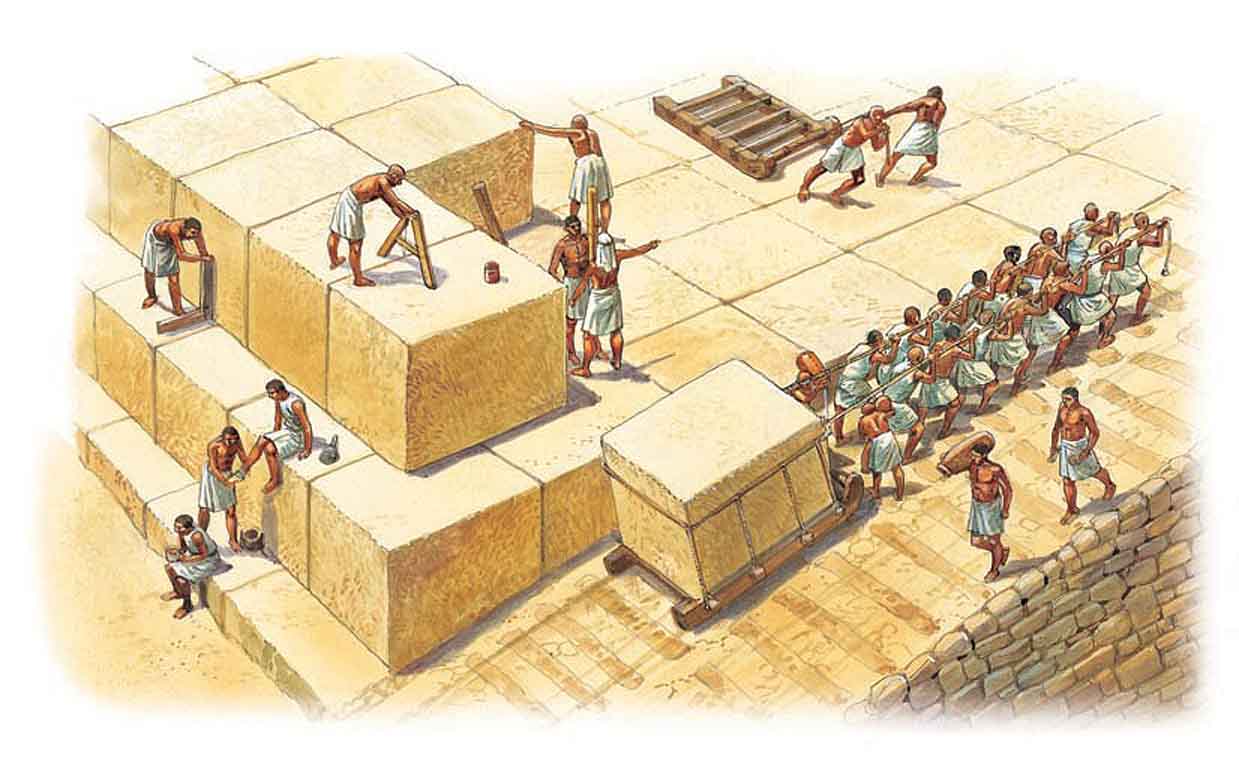

I have worked on a one-hundred million dollar single-family compound in Tiburon – an exquisite sarcophagus. We (the workers) came and left on a shuttle under guard: the security detail was blacked-out SUVs with ex-military dudes in suits and sunglasses. Working that job was like hauling gigantic bricks across the desert, building pyramids for the pharaohs. The supposed apex of residential construction! Ha! I could spit. I worked my ass off and it amounted to nothing. Nothing for me.

You've got to serve someone, but it better be yourself. Live life on your own terms.

Most of us are given very few breaks in life. You have to do it for the love. The love of your art, your craft, whatever. You support your art, your art doesn't support you. If you work hard and you're lucky, you get a pay day. But maybe you still don't. Many artists die as unknown paupers. Gotta do something in-spite of that bleak possibility. Push really hard. You only have one chance. None of us asked to be here, but here we are. We owe it to ourselves to try. Conversely:

We must earn it.

"No, my son, the world does not owe you a living. The world does not need you, just yet; you need the world…

But don’t fall into the common error of supposing that the world owes you a living. It doesn’t owe you anything of the kind. The world isn’t responsible for your being. It didn’t send for you; it never asked you to come here, and in no sense is it obliged to support you now that you are here…

When you hear a man say that the world owes him a living, and he is going to have it, make up your mind that he is just making himself a good excuse for stealing a living. The world doesn’t owe any men anything son. It will give you anything you earn…"

1880 May 6, Sioux County Herald, Advice to a Young Man by Bob Burdette, Quote Page 6, Column 5, Orange City, Iowa. (NewspaperArchive)